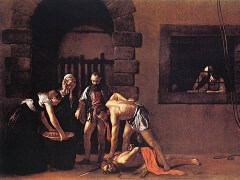

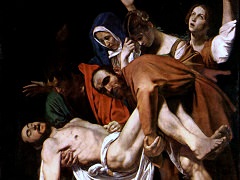

The Seven Works of Mercy, 1607 by Caravaggio

In January, 1606, Pope Paul V conceded a privileged altar to the aristocratic congregation of the Misericordia, founded in Naples five years before. Caravaggio may have been invited there for the purpose of painting the altarpiece.

He carried it out rapidly, between September 23, 1606, and January 9, 1607, when he was paid four hundred ducats for it.

The requirements for the altarpiece were difficult: Caravaggio had to include both the Madonna of the Misericordia and the Acts of Mercy in a single vertical canvas. Traditionally each Act had been represented separately. The few

prototypes combining all the Acts in one picture were North European and inaccessible to him, and none included the Madonna. He set the Acts described in Matthew 25 : 35-36 in a little piazza, perhaps in front of the same Taverna

del Cerriglio where three years later he was attacked. It is night, and the padrone is directing three men to his inn ("I was a stranger, and you welcomed me"). One is hardly visible. The second is recognizable as a pilgrim by his

staff, Saint James Major's shell, and Saint Peter's crossed keys on his hat; perhaps he can be identified as Saint Roch but more likely, following the Gospel, he is Christ in disguise. The third, a young bravo, is Saint Martin c

utting his cloak to share it with the naked beggar in the foreground ("I was naked, and you clothed me"). In the shadow behind the blade is a youth whose legs seem to be twisted ("I was sick, and you visited me"). The group of

loiterers is completed by a husky man, Samson, in the desert of Lechi (Judges 15 : 19), pouring water into his mouth from the jawbone of an ass ("I was thirsty, and you gave me drink"). Opposite this group, on the right, is Pero

breast-feeding her aged father, Ci-mon, through the bars of his prison ("I was hungry, and you gave me food" and "I was in prison, and you came to me"). And in the background, a vested priest holds a torch to illuminate the hasty

transport of a corpse, perhaps recalling the plagues that periodically decimated the city's population (burial of the dead, the seventh Act, not mentioned in the Gospel). Above the scene hover the Madonna and Child with two angels,

as if to warrant divine acknowledgment of human charity, particularly of the protagonists in the painting, who may portray members of the confraternity.

Altogether, it is an ingenious solution to an almost insurmountably difficult pictorial problem. Caravaggio did not accomplish it without some help: Pero and Cimon had already been used in previous representations of the Acts; he

based his angels on a Zuccaro composition of The Flight to Egypt; and Saint Martin's beggar recalls the famous Hellenistic Dying Gaul. Nor did he carry it out without some

revisions: there are substantial pentimenti in the heavenly group and in the area around the heads of Samson and the innkeeper.