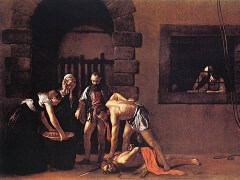

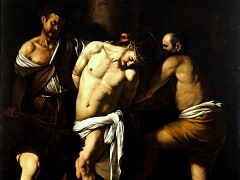

Martyrdom of Saint Matthew, 1600 by Caravaggio

Saint Matthew's history continues with his death. The king of Ethiopia, Hirticus, wished to marry his niece Iphigenia, the abbess of a convent, whose resurrection by Saint Matthew and conversion to Christianity provided the subject for D'Arpino's fresco in the vault. When Saint Matthew forbade the marriage, Hirticus had him killed.

The scene takes place in the foreground of a vast, dark interior, where nearly nude converts to the left and right of a pool await baptism. An altar is in the background. Muziano had painted the subject a few years earlier in the Roman church of Santa Maria Aracoeli, but it was not very often represented. Caravaggio must have been familiar with Muziano's painting and perhaps with a now-lost drawing for the scene made by the Cavaliere d'Arpino while he was still under contract to do the lateral paintings. Caravaggio seems to have been most influenced, however, by more distant works: Titian's famous painting (destroyed by fire in 1867) of The Death of Saint Peter Martyr in the church of Santi Giovanni Paolo in Venice, of which there were many prints in circulation by the end of the sixteenth century; Marcantonio Raimondi's engraving after Raphael's Massacre of the Innocents; and comparable derivative works.

From these sources, all appropriate to a scene of Christian martyrdom, Caravaggio took various poses. He focused on the executioner in the center, at the critical moment when he seizes the supine, helpless Saint Matthew. While Matthew raises his right hand beseechingly toward the executioner, the angel hands down the martyr's palm and the other figures scatter in dismay. We see only fragments of these fleeing figures; light falls jaggedly on them like a strobe, emphasizing their confusion. This outburst of action contrasts with the inaction of the Calling; the movements of those figures seem to be momentarily suspended, while these appear to be congealed in their poses. The pause in the movement of the figures in the Calling is a part of the narrative and contributes to its authenticity; these men in flight, on the other hand, have been portrayed in an instant of continuing action. The executioner and the saint might pause, just before the fatal blow is struck; but the fleeing figures are in precarious, unsustainable poses, so that the effect is artificial, as if the instant of the outburst of response had been quick-frozen.

The confusion of movement and the almost jigsaw pattern of sharply contrasting lights and darks are stabilized by the horizontals of the steps and the altar and by the dim architectural background verticals. Less evident than in the Calling but faintly discernible is an underlying grid composition underpinning the jumble of actions around the central figure. The harshness of the act of assassination is modified by the graceful S-curve connecting the body of the angel through his arm and the palm branch to Saint Matthew's arms. The juxtaposition of the saint's right hand, the executioner's left hand, and the martyr's palm over the Maltese cross on the altarpiece cannot have been accidental; their proximity provides a focus for the meaning of the painting. Perhaps the single candle burning on the altar is symbolic, representing the all-seeing eye of God, ever present and aware of His martyr's sacrifice; it may also refer to the fugitiveness of human life.

The most distant figure is a self-portrait of Caravaggio; it provides a very specific reference point for the viewer, as if Caravaggio were participating in the tragedy, and thus making it contemporary. He looks out at the martyrdom, as if to involve the spectator in it.