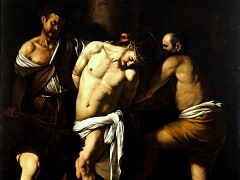

Medusa, 1597 by Caravaggio

No succeeding Italian artist could paint without some evidence of Da Vinci in his works, whether it was intended or not.

One example is Caravaggio's Medusa which was commissioned by Cardinal del Monte, who worked for the Medici family in Rome. According to biographer Vasari, in a document from 1568 da Vinci also created a Medusa shield that was

in the Grand Duke's collection. If this is indeed the case, del Monte would certainly have known about it and instructed the young artist to follow the master.

Caravaggio painted two versions of the Head of Medusa. The first in 1596 and the other presumably in 1597/8. The first version also known as Murtula, due to the poet who wrote about it (48x55 cm) is signed Michel A F, (Michel

Angelo Fecit) and was found on the painter's studio only after his dead. Nowadays it belongs to a private collection whilst the second version, slightly bigger (60 x 55 cm) is not signed and it is in the Uffizi Gallery, in Florence.

The "Head of Medusa" executed by Caravaggio, in 1598, was commissioned as a cerimonial shield by Cardinal Francesco Maria Del Monte, the Medici family's agent in Rome, after seeing, on the painters studio, the first version - The

Metula painting. The purpose of this commissioned was to symbolize the Grand Duke of Tuscany's courage in defeating his enemies. For its subject matter, Caravaggio drew on the Greek myth of Medusa, a woman with snakes for hair who

turned people to stone by looking at them.

Medusa was a Gorgon monster, a terrifying female creature from the Greek Mythology. While descriptions of Gorgons vary across Greek literature, the term commonly refers to any of three sisters who had hair of living, venomous

snakes, and a horrifying visage that turned those who beheld it to stone. Traditionally, while two of the Gorgons were immortal, Stheno and Euryale , their sister Medusa was not, and was slain by the mythical hero Perseus, the

legendary founder of Mycenae and of the Perseid dynasty. According to the story, she was killed by Perseus, who avoided direct eye contact by using a mirrored shield. After Medusa's death, her decapitated head continued to petrify

those that looked at it.

Caravaggio plays with this concept by modeling himself for Medusa's face - making him the only one who is safe from Medusa's dedly gaze - and having to look at his reflection to paint the shield in the same way that Medusa caught

her own image moments before being killed. Although Caravaggio depicts Medusa's severed head, she remains conscious. He heightens this combination of life and death through Medusa's intense expression. Her wide-open mouth exudes

a silent but dramatic scream and her shocked eyes and furrowed brow all suggest a sense of disbelief, as if she thought herself to be invincible until the moment. But Caravaggio's Medusa does not have the full effect of scaring

the viewer, since she does not look at us, thereby transferring the power of the gaze to the viewer and emphasizing her demise.

Caravaggio displays huge technical achievements in this work by making a convex surface look concave and Medusa's head appear to project outward.