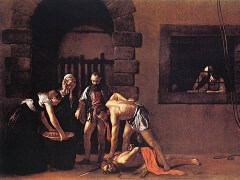

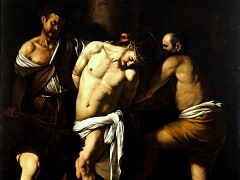

Judith Beheading Holofernes, 1599 by Caravaggio

Judith Beheading Holofernes tells the story Biblical story of Judith, who saved her people by seducing and beheading the Assyrian general Holofernes, which was a common theme in the 16th century. The same story has also been

painted by artists such as Sandro Botticelli, Donatello, Artemesia Gentileshi, Giorgione, and Andrea Mantegna. Caravaggio was certainly aware of Judith's traditional identity as a symbol of triumph over tyranny; but he presented

the subject primarily as a melodrama, choosing the relatively rarely represented climactic moment of the actual beheading of Holofernes. Judith, young, beautiful, and physically weak, draws back distastefully as she seizes

Holofernes's hair and cleaves through his neck with his own sword. Holofernes, on his bed, powerful but drunk, nude, and bellowing helplessly, has frozen in the futile struggle of his last instant of consciousness. The bloodthirsty

old servant, popeyed as she strains forward, clutches the bag in readiness for the disembodied head. It is a ghastly image, with primary interest in the protagonists' states of mind: the old woman's grim satisfaction, Holofernes's

shock, and Judith's sense of determination. Caravaggio intensifies the body language not only in the poses, gestures, and facial expressions but also in the clenched hands. Drama has displaced the charm of his earlier epicurean

paintings, as if the world had ceased to be his oyster and become a battlefield.

If the figures have become static, they continue to be made of convincingly solid flesh, displacing space. But the voids around them are at least as black and two-dimensional as they are empty and three-dimensional. The picture

resembles a photograph taken with a wide-angle lens, unfolding panoramically rather than penetrating depth within a single frame of vision. The starting point, strangely enough, is the least important figure, the servant, whose

precisely profiled head- in relief rather than fully rounded - implies a viewpoint from in front of the right edge of the painting rather than from the center. This peculiarity was probably the result of Caravaggio's having not yet

fully developed the technique of rendering on a two-dimensional surface the effect of vigorous action within fully convincing three-dimensional space. Or conceivably the painting was designed to be seen from the right, and he was

already experimenting with anamorphic composition. The influence of Da Vinci is apparent in Caravaggio's Judith Beheading Holofernes. Here, the grotesquely intense face of the old

crone holding the bag for Holofernes's head is undeniably evocative of da Vinci's caricatures.