The Fortune Teller, 1599 by Caravaggio

According to Mancini, Caravaggio painted this picture while he was staying with Monsignor Petrig-nani and sold it cheap - for eight scudi. When Mancini wrote (c. 1620), it belonged to Alessandro Vit-trice, but by 1657 Scanelli had

seen it in Prince Camillo Pamphili's collection.The prince sent it as a present to Louis XIV when Bernini visited Paris in 1665. Damaged en route, it was received with no great enthusiasm. By 1683 it was in Versailles, where it

remained until the French Revolution, when it was transferred to the Louvre.

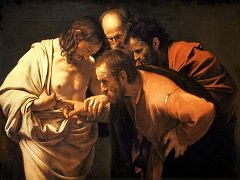

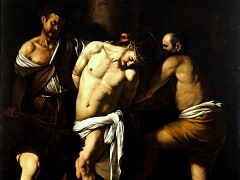

Mancini described the action as "a gypsy girl . . . telling a youngster's fortune. . . . [She] demonstrates her roguishness by faking a smile as she removes a ring from [his] finger. . . . he, by his naivete and libidinousness,

unaware that he is being robbed, smiles at her." The theft is barely visible; it does not appear in the other version. Although her neatness and her well-scrubbed look may be less than authentic, the girl's voluminous cloak tied

over one shoulder and her linen turban and blouse are historically correct. They were first described in France in 1421, and gypsies continued to wear them until the end of the seventeenth century. Fortune-telling was also a

customary gypsy trade, although raffish, as is made obvious by her suggestive caress of the mount of Venus on the boy's palm.

With his usual hyperbole, Caravaggio's friend Gaspare Murtola asked rhetorically in a 1603 madrigal on the painting: Who is the more deceptive, the gypsy or the artist? Caravaggio was no less seductive with his brush than she with her sweet talk and nimble fingers. It is a charming picture, but the space is somewhat ambiguous, as if Caravaggio had not yet solved the riddle of representing three-dimensional forms on a flat surface. And there are a few lapses in verisimilitude - in the doublet, for example, and in the hilt of the boy's rapier. The system of light is the most complex that Caravaggio had yet attempted. The source, a window to the left reflected in the hilt of the rapier, illuminates the whole space and much of the back wall. The streak of shadow between the two streams of light sug-gests a curtain half-drawn above a sash. But this background illumination has been adjusted to contrast with the figures' forms. It also casts the gypsy's face a little mysteriously into shadow and brings the boy's innocence into full light. Most of all, the light is silvery and lyrical, radiant as the youth and as pretty and transparent.