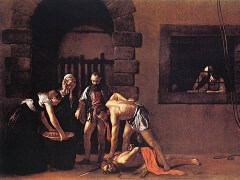

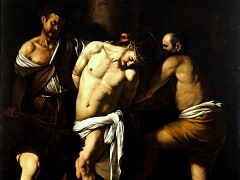

The Adoration of the Shepherds, 1609 by Caravaggio

In The Adoration of the Shepherds, the scene is another dark

interior, with a beam of light cutting across from the left, causing

the figures to emerge from the general obscurity. The composition is

ingenious but unobtrusive. Its effect is of restraint, tranquility,

and calm immutability.

Doctrinal implications are understated. Perhaps by seating

the Madonna on the ground Caravaggio was deliberately recalling the

late medieval play on the Latin words "humilitas'' (humility) and

"humus" (earth). But the Madonna's humility speaks for itself. She

is no queen of heaven, but a simple healthy young woman of the

people, cuddling her baby like any other mother. Nor does anything

suggest the shepherds' historical significance as the first men to

recognize Christ. Only the young man in the center makes a prayerful

gesture and even that is equivocal. They may be surprised to find

this mother and her beautiful newborn child in this shack, but their

response is to admire them rather than to venerate the Virgin and

worship Christ.

No cloud of angels bursts in, no great blaze of light

disturbs the tranquility, and accessories are meager and plain. The

basket containing the Holy Family's simple travel necessities - a

loaf of bread, a few pieces of cloth, and Joseph's carpenter's tools

- is unpretentious, and its sparseness emphasizes the family's

simplicity and poverty. Some theological significance might lie

concealed within the other accessories, but they appear primarily as

still-life details. The building is a roughly built farm shed,

evidently not intended for human habitation. The traditional ox and

ass seem to belong in this barn, placidly feeding from the manger.

Nonetheless, the subject, even without the halos marking

Mary and Joseph, is unmistakable. Though unadorned, it lacks none of

its essential earthly components. Caravaggio deliberately avoided

any eloquence within it, as contradicting the homespun authenticity

of the wonder at the miracle of birth. The dignity that he has

recognized in these simple people in this drab setting conveys his

sense of their worth, not primarily as participants in this central

Christian event but as universal goodhearted common folk.